How Much Bandwidth Do You Need?

Over the past few months, the team at Center for Data and Computing (now the Data Science Institute) has been working with the City of Chicago and community partners to identify technical questions about broadband performance that we might be able to answer.

One important question is, how much bandwidth households need. Policymakers need this information to define thresholds for “adequate” broadband for users now and in the future. From policymakers, this is a question about the threshold that should define “adequate” broadband – for users today and in planning for future networks. Community members have echoed this with a more practical refrain: “my connection is not fast enough.”

In this post, I’ll describe three ways for thinking about that question:

- How much do households and services use in practice?

- At what bandwidth do critical applications actually fail?

- What do ISPs suggest, and what do applications claim to require?

Here’s the basic answer:

- For most people, video streaming and conferencing (Zoom & Google Meet) are the most-intense uses of their home Internet connection.

- Those services generally consume and require about 1 Mbps in each direction of transmission. (Obviously, streaming is one-way while conferencing is two-way, if your video is on.)

The standard definition of “broadband” is “25/3” – 25 Mbps down and 3 Mbps up. If you have two people in simultaneous meetings, that means 2 Mbps each way; 3 people could use 3 Mbps. That will not saturate a “basic” broadband link in the downstream direction, but if everyone is in a meeting at the same time, you can saturate the upstream link. Streaming HD video or rapidly downloading large files (many gigabytes) requires greater bandwidth. However, for most people this is rare.

This raises an important conundrum. If 25/3 is “usually good enough,” why is it sometimes not? What is the issue when conferencing fails? For whom does it fail? Identifying the conditions that are experienced as poor performance, is the aim of our work with the city and partners, just funded by data.org.

How Much Bandwidth Do We Consume?

Consumption in My Home

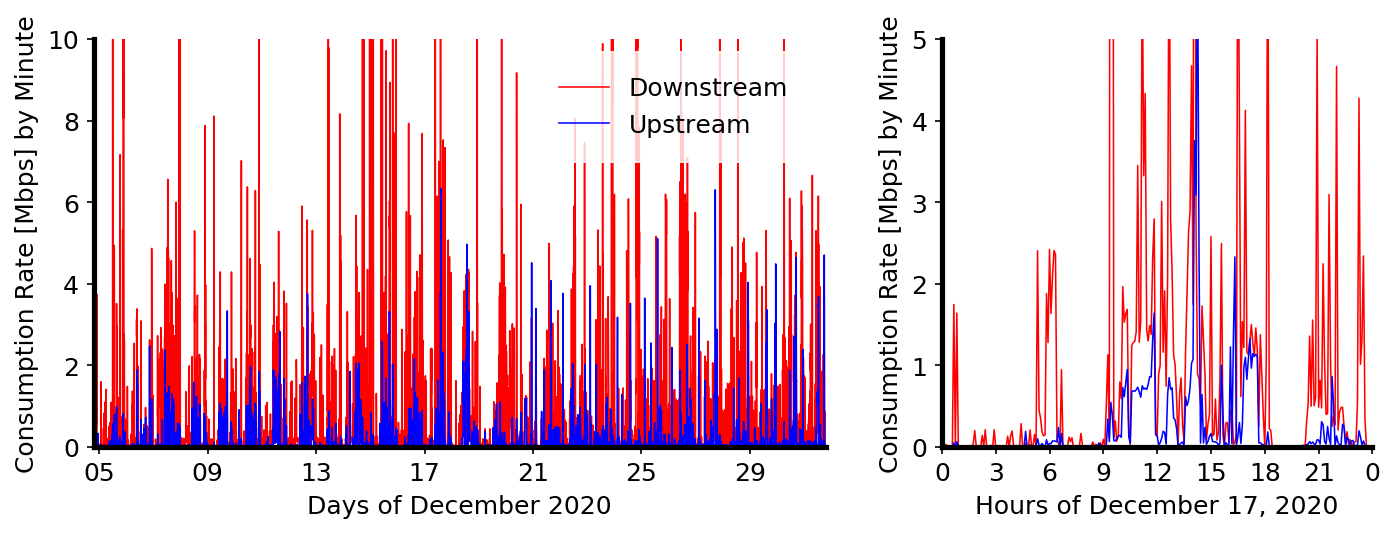

The first way to ask what is needed, is to ask how much we use practice. In a recent post, I described methods for measuring Internet consumption at home. Let’s start with a look at those results – consumption for my family in December, as we hunkered down from covid with my in-laws. This is a four-adult household on an unconstrained (100/10 Mbps) connection, with two people working remotely. On the left-hand side is the trend for the entire month, and on the right-hand side is a single, high-intensity day.

Consumption rates are in megabits per second, in one-minute intervals. The blocks of continuous use are video conferences. You can see that high upstream bandwidth (sending video) is usually paired with high downstream consumption. These blocks are usually 1 Mbps high, though sometimes it’s 2 or 3 Mbps – multiple people conferencing. In short, the typical, high-intensity behavior of a single video stream requires 1 Mbps, averaged over any moderate time span.

Of course, Internet consumption is not smooth; it is peaky. You click, and you want the result now. The reason that video is not that resource-intensive for a single connection at a given moment, is that while the data volume is large, you have a fairly long time to receive it. When you download a very large file on the other hand, it can really stress your bandwidth. Video conferencing can’t do that, since your computer can’t download what the other person says until they say it. But video streaming can. Your computer typically buffers the next minute or so of a video when you load the page, so that your playback is smooth. If I load Netflix from scratch, the bandwidth over the first ten seconds reaches 14 Mbps, but averaged over 5 minutes, the consumption drops to just 0.7 Mbps. After that initial burst, the bandwidth is “fairly low,” and so more is available to others in my household.

You see those as the spikes on the single day, with bandwidth well more than 10 Mbps. In practice 25 Mbps connections are adequate, however. Increasing downstream bandwidth improves download speeds. Increasing upstream bandwidth allows for more simultaneous upstream links on the connection.

Consumption Across America

Perhaps my own household is not typical, so let’s turn to national data on internet performance from SamKnows and the FCC.

SamKnows installs “whiteboxes” in several thousand households across the country, with an exhaustive suite of measurements that includes consumption. (For a description of these and other datasets on Internet use, see my post on public data.) The downside of the SamKnows’ data is that consumption is only recorded in hour-long segments. That means that all we can see are how much people use over very long periods. Given the peaky nature of Internet traffic, that’s not all we’d like. Bearing this limitation in mind, how much bandwidth do households use?

To study this, I pulled the highest-intensity hour for received and transmitted traffic in each day for each SamKnows household, in 2020. On any given day, the median household maxes out its hour-averaged downstream use at about 1 Mbps – roughly consistent with the numbers seen for my own household. Again, an hour is a very long average as compared with patience while browsing, and households might require more at some point over a month. Among households, the median highest-use hour over a month was 4.9 Mbps, and over the eight months available for 2020, it was 9.6 Mbps. At the high end, 10% of households used at least 57 Mbps continuously (averaged over an hour) at some point in the first eight months of 2020. However, at this point, we’re considering a lot of maximums: the highest use-hour over eight months of hours, by power users. You can take your pick of quantiles and aggregation periods, below.

| Quantile | Household Days [Mbps] |

Max by Month [Mbps] |

Max for Jan-Aug 2020 [Mbps] |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0.25 | 0.1 | 1.8 | 4.3 |

| 0.50 | 1.0 | 4.9 | 9.6 |

| 0.75 | 3.8 | 10.8 | 20.6 |

| 0.90 | 7.3 | 24.2 | 56.8 |

| 0.99 | 25.9 | 121.8 | 208.2 |

There’s another lesson in this analysis, however. While people do tend to use resources at the same times (for instance, watching Netflix in the evening and not in the middle of the night), their very-highest moments of use are not exactly aligned (my schedule of teleconferences is not the same as my wife’s). This suggests potential in sharing connections within apartment blocks, for instance.

At What Bandwidth Does Video Fail?

Let’s now turn our second way of evaluating bandwidth needs: reducing bandwidth until applications become unusable.

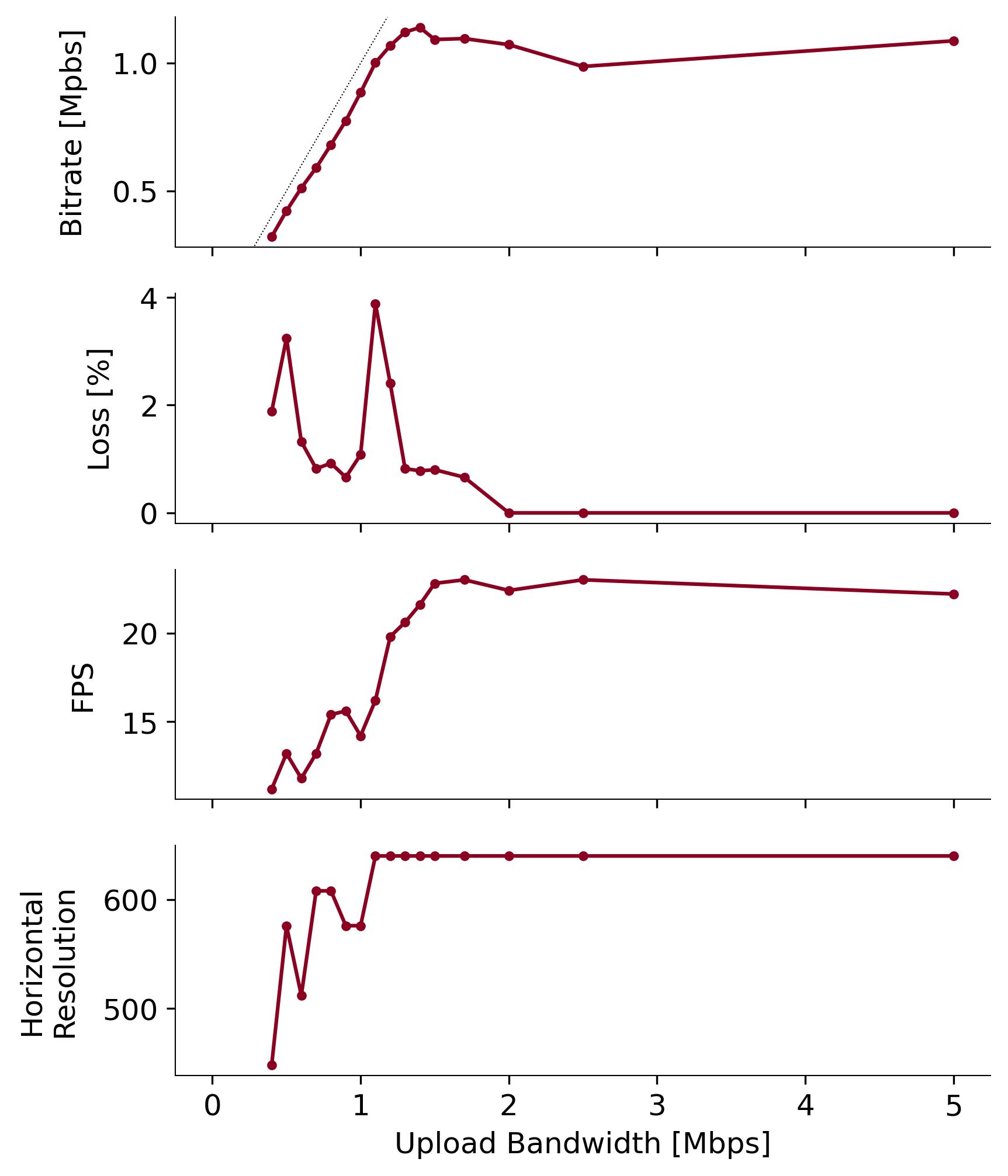

I’ll focus on video conferencing – a critical application throughout the pandemic. In short, what we do is start a meeting with a remote host – my desktop at the University, and connect to that meeting from another test machine. We then manipulate the connection using “traffic control” (tc) and measure the framerate, resolution, and bitrate in the Zoom API and Google Audit Logs.

Above, you can see Zoom performance as a function of upstream bandwidth. Below 1.5 Mbps, bandwidth, frames per second, and resolution drop, while packets begin to get lost. So there is a meaningful loss in performance when bandwidth drops under about 1.5 Mbps.

What Do ISPs and Services Say?

Now that we have some context about the Internet that Americans tend to use, let’s compare this to what the Federal Communications Commission (FCC), Internet Service Providers (ISPs), and content providers suggest.

The FCC provides a table of requirements by category. SD video requires 3-4 Mbps, HD video requires 5-8, and 4K requires 25 Mbps. These estimates are substantially higher than what I saw, clicking on a basic show on Netflix. They list 5-25 Mbps as the minimum for telecommuting, but list standard video calls at 1 Mbps (consistent with what we saw). To my mind, it’s not clear what the other 24 Mbps are supposed to be. Usually, editing documents etc. requires less bandwidth!

Big downloads are not included among the services below, but it’s an important (if uncommon) use. For this, we just have to consider what the basic unit of speed – Mbps, megabits per second – means. A bit is one eighth of a byte, so a megabit (Mb) is one eighth of a megabyte (MB). A gigabyte is 1000 megabytes. Given 60 seconds in a minute, a 25 Mbps connection amounts to:

25 Mbps = 25 (Mb / second) (MB / 8 Mb) (60 seconds / minute) (GB / 1000 MB) = 0.1875 GB / minute

In other words: it takes about 5 minutes to download a 1 GB file on a 25 Mbps connection. A 5 GB file takes 25 minutes on 25 Mbps, or 7 minutes on a 100 Mbps. But how often do you do this?

Zoom requires 0.6 Mbps (up and down) for “high-quality video,” and 1.2 Mbps for 720p HD video. Group calls require more: 1.0 Mbps down and 0.8 Mbps up. Gallery review requires yet more: about 1.5 Mbps. Zoom does also list 1080p HD video (3 Mbps), but even on the University of Chicago’s plush connection and Zoom contract, I rarely see streams with resolutions higher than 640×360. So that HD doesn’t happen much, and it’s usually determined by Zoom, and not your connection.

Google Meet suggests 1 Mbps for 2 participant in HD and 2 Mbps for 10 participants. HD requires more of course – 2.6 Mbps for 2 participants, and 4 Mbps for 10 participants. When I have examined Google Audit Logs for my own meetings, I typically use around 0.8 Mbps.

YouTube recommends sustained speeds between 0.7 Mbps for 360p SD and 20 Mbps for 4K. In between, good SD (480p) is 1.1 Mbps and basic HD (720p) is 2.5 Mbps.

Hulu suggests that you need 4 Mbps for their general library, 8 Mbps for live streams, and 16 Mbps for 4K video. They offer as an italic footnote that “viewers may be able to stream at a reduced video quality with 1.5 Mbps.”

The big question to take away from the video sites is: how much HD video do you expect to actually watch? In my experience – clicking around to run these tests, few sites are actually providing most of their content at 4K. Do you need it? Why pay for it?

AT&T’s site initially lists their lowest connection at 100 Mbps Internet, offered for $35 per month (small print: plus $10/mo. for equipment). They list a 300 Mbps connection as “perfect for work & play on multiple devices.” If I try to click through to buy this, it seems those options aren’t available, and I am offered 25 Mbps for $55 per month plus taxes for the first 12 months and $65 a month after that (!). There’s a lot to unpack in that – suspect advertising and up-selling – but the 100 Mbps connection just isn’t in-line with what we’ve see applications really using.

AT&T also provides a calculator, based on the FCC’s table. As inflated as the FCC’s table seems to me, this is at least more realistic. Using their calculator, my recommended bandwidth was 10 Mbps. But you can try it at their link!

Comcast xfinity offers a tool suggesting how much you need. They ask “how many devices connect to your network at a time,” admonishing the user to “Think smartphones, computers, tablets, smart speakers, thermostats, etc.” This is a bizarre equivalency between thermostats (which do not stream HD video) and person-centered devices (which may or may not). But if I follow their instructions, my household sees typically sees up to seven devices at a time (two computers, a smartphone, three chromecasts, and a printer). If I then click “Web browsing and email” and “Streaming shows and movies” Comcast recommends 200 Mbps. That is an expensive suggestion, and it’s simply not consistent with any of the data above.

Verizon FiOS lists its lowest internet package at 200 Mbps. There’s not much to say here, except that it’s probably more than you need.